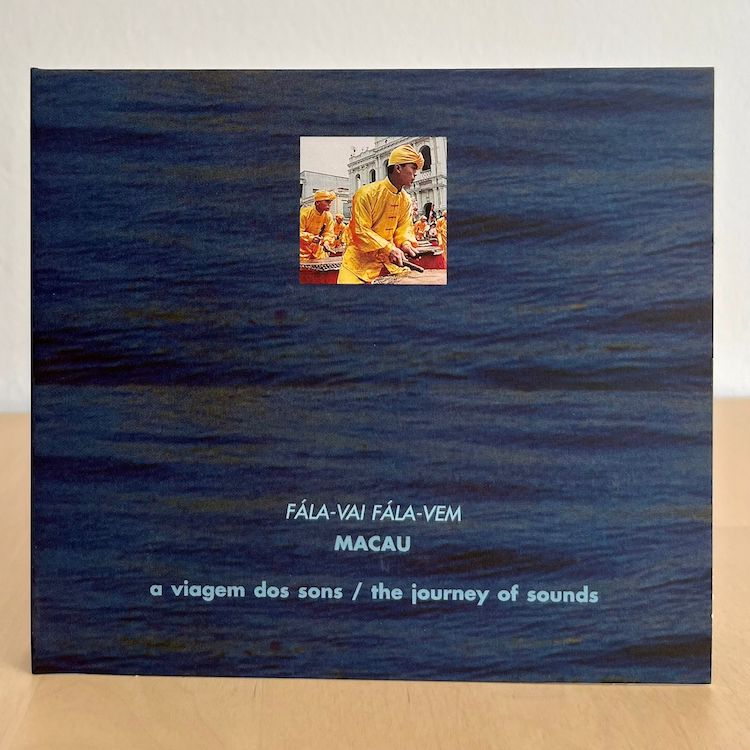

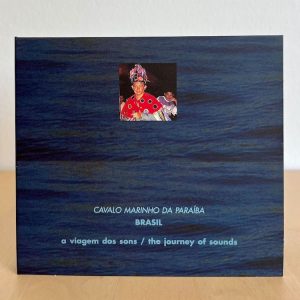

A Viagem dos Sons – Fala-Vai-Fala-Vem

5,00€ – 15,00€

[zoomsounds id=”fala-vai-fala-vem”]

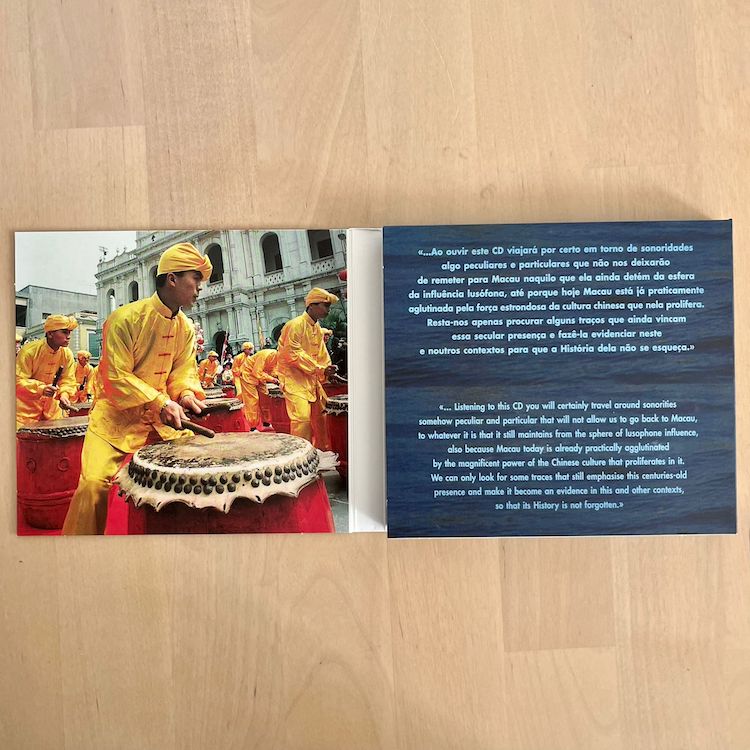

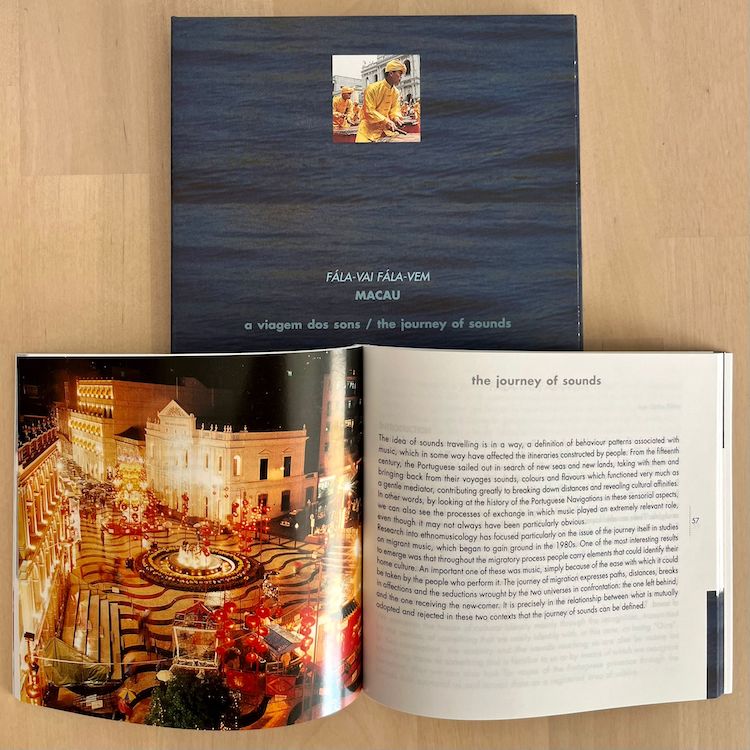

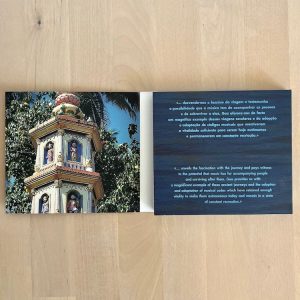

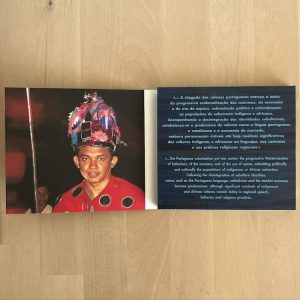

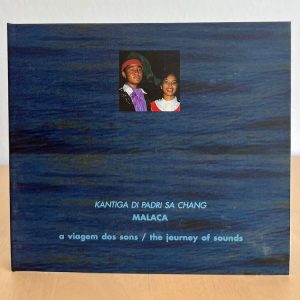

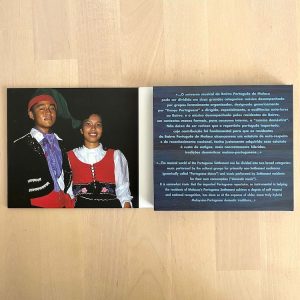

Deluxe digipack edition with trilingual booklet (written in Portuguese, English and Patois), featuring 116 coloured pages.

A lusophone arriving in Macao today (1998) will surely notice and wonder about the feeble presence of cultural traits of Portuguese influence, mainly on the linguistic level. Listenig to someone speak Portuguese seems accessible only to someone who has a family member or friend who will guide them through the small spaces that are still ocupied by the Portuguese community living there. However things weren’t always like this. Once Macao had a notorious lusophone presence. We are aware the Portuguese were never, in the history of Macao, a majority population, however their political and administrative dominion allowed them to develop a peculiar “singularity” of lusophony, confined to the conquest and influence of privileged spaces that range from architectural references to their interference in the habits of their social network. On this regard, we will have to mention the importance of the so called “Children of the Land” Macanese, as a result of the miscigenated legacy of the Luso-Asian mix that has perpetuated through time and space, through consecutive generations who never denied their Portuguese identity. The role of Creole dialects, also known as “patuá”, are without a doubt a form of expression of the cultural adapations of varied influences. Mostly these forms tend to reflect a peculiar sound in which the presence of a certain native language can be altered and sometimes adulterated, due to context, gaining a certain meaning for those who speak it and a logical sense in that context. That’s how the reference to the “Macanese patuá” takes shape.

This is clearly not the place to comment the origins of the linguistic structure of this characteristic “patuá” that can still be found in the more traditional Macanese houses. All of the recorded production (that we are aware of) in “Macanese patuá” gravitates aroud two main themes – nostalgia and satire – which is indicative of its element of social intervention that uses those two forms of action to provoke both the enhancement of the feeling of belonging and social critique. Mentioning “patuá” to identify the traces of the lusophone presence in Macao is in itself a binding element of the possibilities of analysis raised by this subject. The tracks included on this collection are also an example of that. If this talking and singing Creole hadn’t existed, it would have been almost impossible to release a record that evoked the presence of peculiar and “sui generis” sounds of the Portuguese influence on this trip of the sounds, that also goes through Macao. As for its importance as an element of cultural identification, all we have to say is that to this day some people still consider that one has to speak “patuá” to be a Macanese, thus enlightning the process of enculturation in learning this distinction requirement. It is also clear that the “Macanese patuá” has a role in the way the group externalizes and distinguishes itself from the other, allowing them to speak a language that only “the insiders” know. Thus the still visible reminiscences of a certain categorization of the Macanese community’s ostracist character. Let’s now go more throroughly through some relevant facts that contributed to the cultural miscigenation of Macao and therefore the cultural basis of the “Macanese patuá”.

| Weight | N/A |

|---|---|

| FORMATO | CD, MP3 |

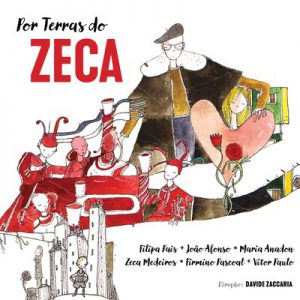

Related products

Discos

Discos

Discos

Discos