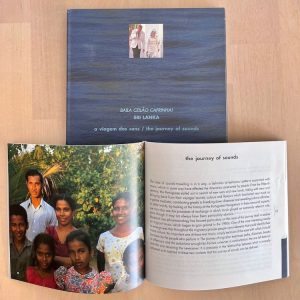

A Viagem dos Sons – Baila Ceilão Cafrinha

5,00€ – 15,00€

[zoomsounds id=”baila-ceiao-cafrinha”]

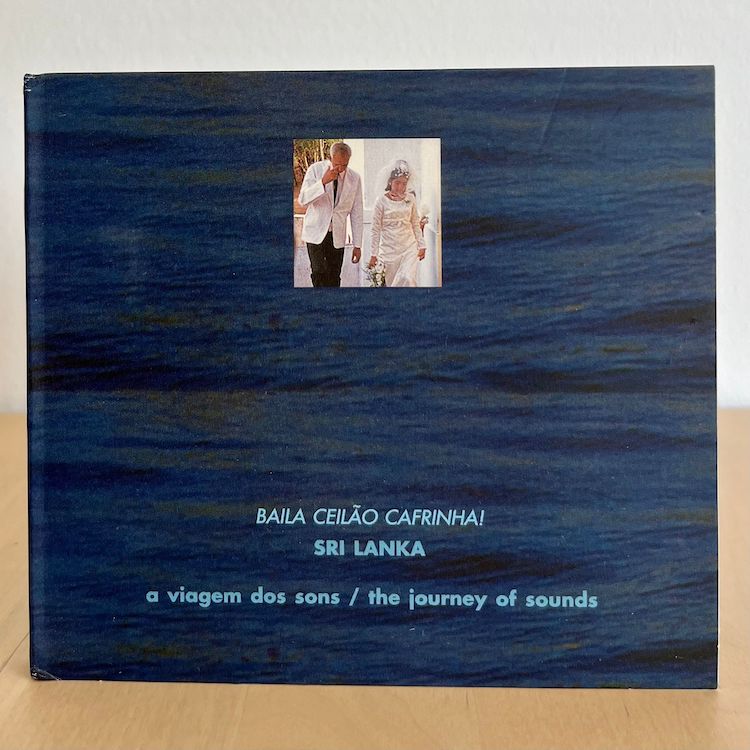

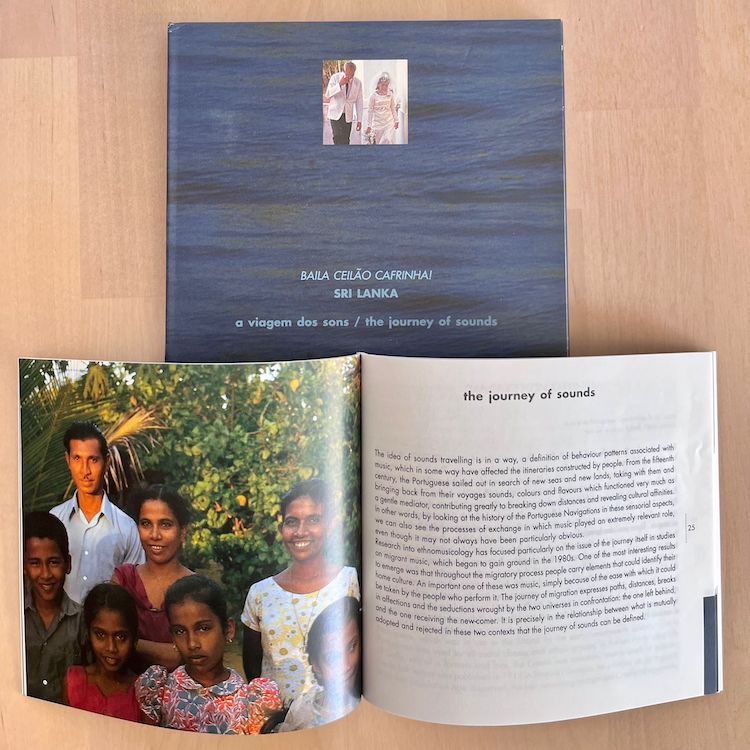

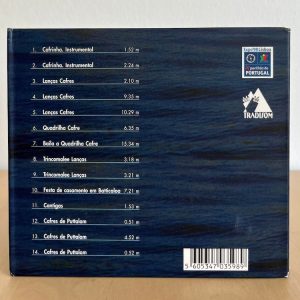

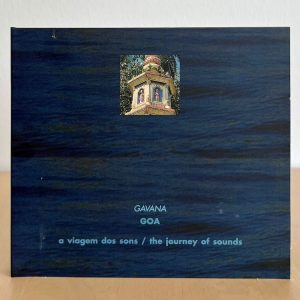

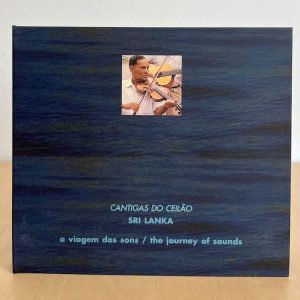

Deluxe digipack edition with trilingual booklet (written in Portuguese, English and Creole), featuring 86 coloured pages.

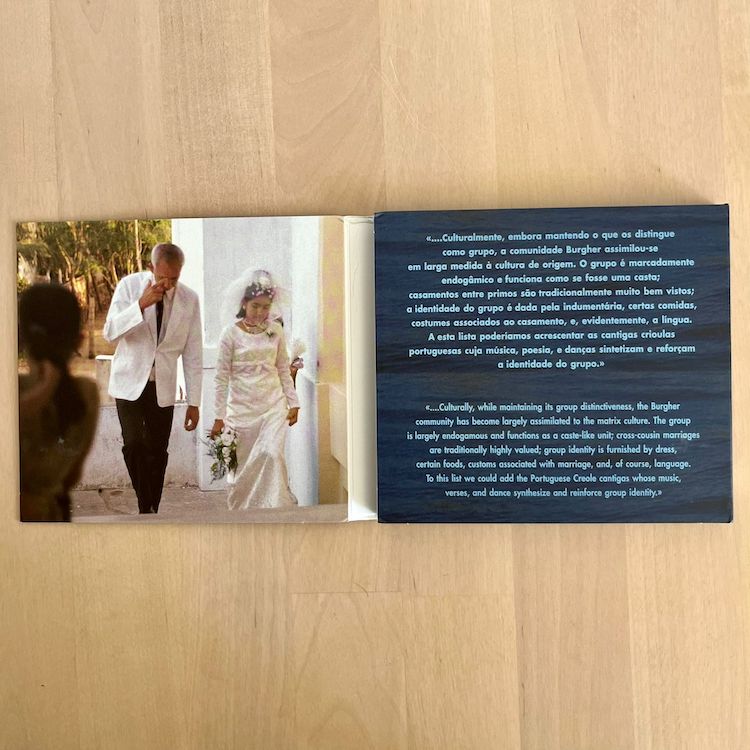

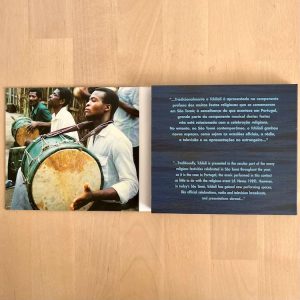

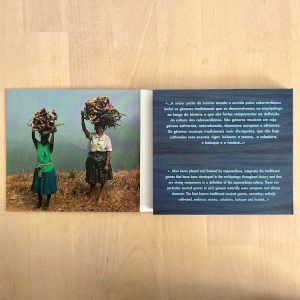

Burghers or Portuguese “Mechanics”. Throughout the Dutch period, the miscigenated descendents of the Portuguese were originally known as «Burghers», but even then they were considered racially and economically inferior and used to be popularly nicknamed as “mechanics” or “micos”. They spoke Portuguese Creole that spread throughout the island, from the communities of African and Euro-Asian mestizos that served in the fortresses in the early 17th century. The fact the Burghers were poor and isolated seemed to make them want to identify with «Portuguese» tradition and feel proud to speak and sing in «Portuguese». English linguist Ian Smith lived in Batticaloa in 1973-74, among the Portuguese Burghers of the East Coast, while he worked on his research for the book Sri Lanka Creole Portuguese Phonology, in which he cites statistics that indicate that in 1971 2255 Burghers lived in District of Batticaloa and 1676 lived in the village of Batticaloa. Cafres, known in Sinhalese as kapiri or kapili, initially reached Sri Lanka along with the Portuguese, probably in the decades of 1620 and 1630, and are probably the topazes, brought from Goa, to which the Portuguese documents from the fortresses of Batticalia and Trincomalee refer to. Throughout the Dutch period, cafres were free to marry the descendents of Portuguese on the island. In the 18th century the Dutch organized them to work, either as slaves or as militias. Because the Dutch word Burgher also applied to anyone with European mixed blood, the Portuguese were usually included in this category which is still used in Government census. In contrast with the Dutch Burghers, who created an exlusive Dutch Civil Union in 1907, in 1975 the Portuguese from the lowest class were still called «micoburghers», keeping up with the tradition of referencing their «mechanical» talents in their craft occupations.

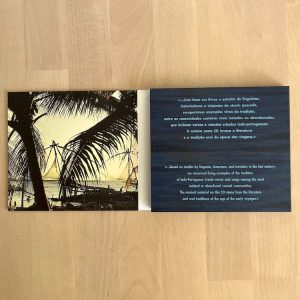

The influence of the music of the Portuguese communities in Ceylon is approached by C.M. Fernando in The Music of Ceylon. The songbook «Kaffrein-Neger Song Portugeise” highlights the contribution of the cafres of Western Africa in Creoule folklore and in Portuguese culture in Sri Lanka. Whatever the word used, kafferinhoe, kaferingha, kaffiringha, cafferina, etc., that type of rhytmic music, whose transcribed verses came to light in 1870-80, can still be heard in Sri Lanka a century later, although its pratice is increasingly rare and bordering exctintion.The recording of music by the cafres of Putalão represents the last known case of Afro-Sinhalese music in Ceylon. In popular culture, the rhythm and melody of the traditional cafrinha have been adapted and incorporated in Sinhalese popular music, now known as baila. As a result of recent cultural syncretism, as time goes by and Portuguese culture is even more assimilated, the baila – of Portuguese – origin starts to be known as a Tamil street dance. However cafrinha is still associated to the decadent reputation of the festivities of Portuguese Burghers, represented on the cover of a recent popular album through a drawing of scruffy people with brandy bottles, playing and dancing with women.

| Weight | N/A |

|---|---|

| FORMATO | CD, MP3 |

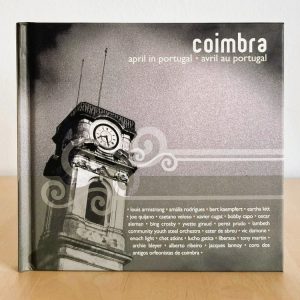

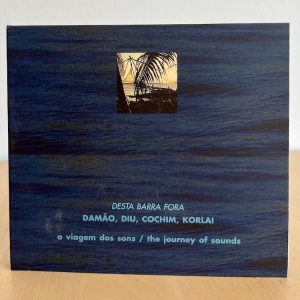

Related products

Discos

Discos

Discos

Discos

Discos