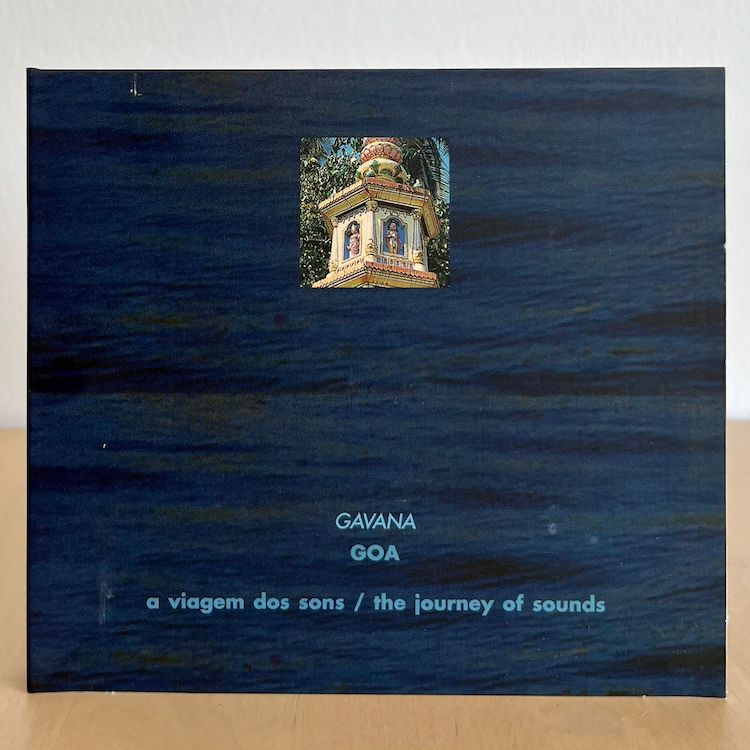

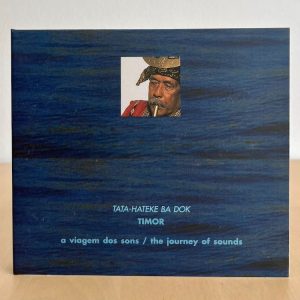

A Viagem dos Sons – Goa

5,00€ – 15,00€

[zoomsounds id=”goa”]

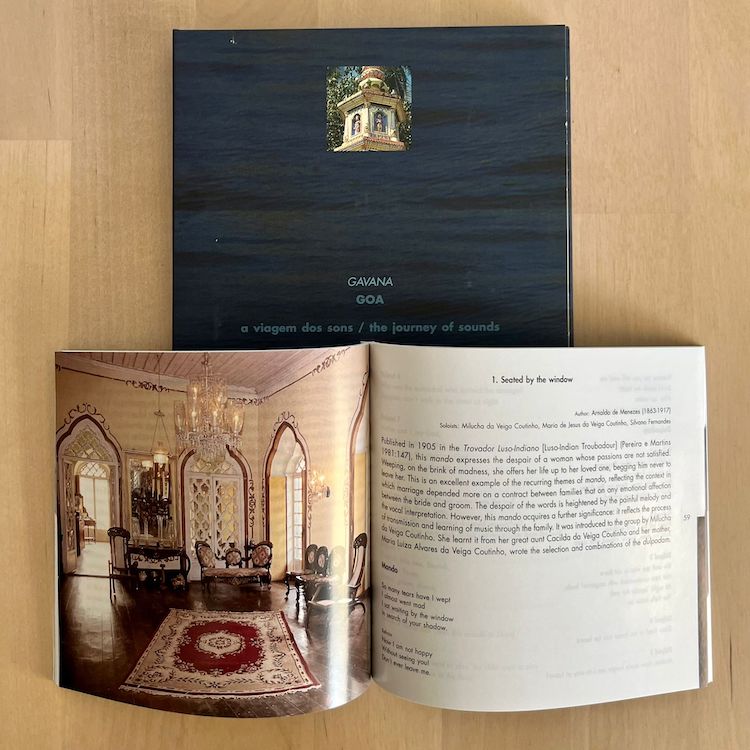

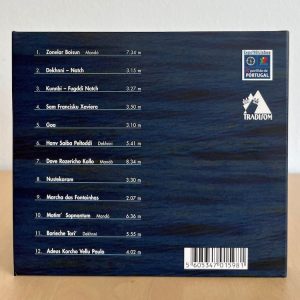

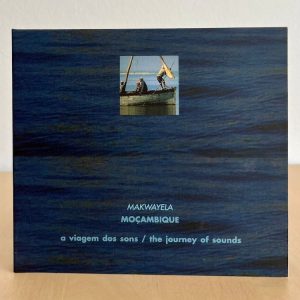

Digipack luxury edition with a trilingual booklet (Portuguese, English and Konkani) with 122 coloured pages.

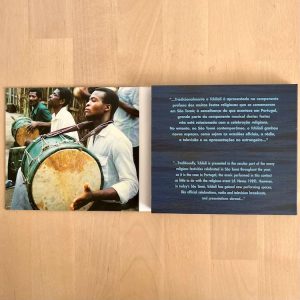

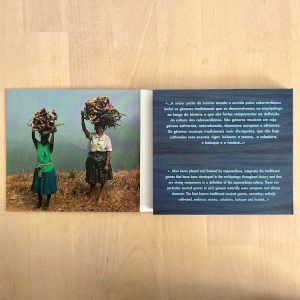

Music and dance in Goa are a good reflection of the plurality of expression and processes we have described before. Its pratice is also associated with caste, meaning each caste owns their own repertoire. Hindus and catholics clearly distinguish the type of music they perform. Common to both groups is the existence of two registers: erudite tradition and popular tradition.

The songs collected on this CD are an excellent example of the multiple musical processes that allows to define the category “Goan music” and the context of “music in Goa”.

Mando and dulpod (nº1, 7, 10, 12) are the most elaborate form of non religious harmonic chant and a perfect representation of the typical repertoir of catholic brahmins and chardós.

Mando tells a delicate tale of love and longing, with a deep dolence contrasting with the joy and playfulness of dulpod. Dulpod tells us other stories: everyday tales, jokes, rumour, curiosity and the most mundane aspects of Goa’s ambients and experience.

The fact that dulpod comes after mando has to do with dance, as both these songs can be equally danced, something that was almost mandatory at catholic wedding until de 60s. Dekhnni (numbers 2, 6 e 11) is the best example of an interception between hindy and catholic realities. It’s a sung musical genre, originally danced by the «bailadeiras» (a name given by the Portuguese to devadassi women) and it was forbidden by the catholic church which also disapproved of the presence of its protagonists in any hindu festivity.

However dekhnni survived every prohibition and is still sung and danced today by catholics. It appropriated the tonal harmony and transformed its interpretation according to the musical references of its new interpreters. A more careful approach will define contemporary dekhnni as a song made by catholics about an aspect of hindu reality, once so socially disapproved but consequently so seductive too. Some of the musical ingredients but mainly the dance scan that other side of Goa, closer to India through the luxurious costumes, the ornaments and the sensuality of the body in it.

The proposal of the Gavana group on this record agglutinates the several processes that may define the context of music in Goa. On one hand it indicates an intense musical experience by reinterpretating dances and songs that – in their most part – belong to the familiar repertoir of the group’s elements; by lending that same repertoir a more sofisticated instrumental and vocal organization, on the other hand, it presents us a recent reality in Goa, defined by the formation of groups devoted to stage performing; finally, by including on this record a new composition (number 5), authored by its musical director, it also expresses the singular concept that Goans themselves have of traditional music: it’s not exclusively confined within the past but it looks for renovation, aknowledging that contemporary composers are also capable of building tradition.

The release of the first CD of Goan music recorded in India is a landmark of a long journey built around emotions, challenges but also some turmoil. This record allows us to access the sound, the words and the voices but also conceals all the scenic, coreographic, gestural and contextual facet that define music and that are crucial ingredients to identify «Goan music».

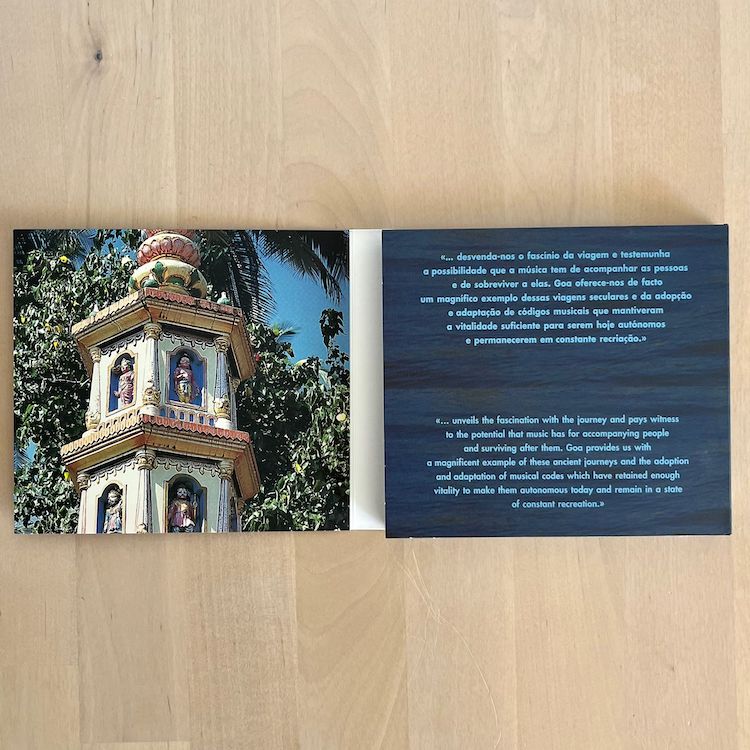

So, regardless of the irreplaceable value of the CD and these recordings, this is still a reductive reading of the expressive behaviour that we call music, although on another level this document is surprisingly revealing: it unveils the fascination of the journey and is a witness of the power of music to accompany people and to survive them. Goa is indeed a magnificent example of those secular journeys and of the adoption and adaptation of musical codes that have remained vital enough to keep autonomous and in constant recriation.

| Weight | N/A |

|---|---|

| FORMATO | CD, MP3 |

Related products

Discos

Discos

Discos

Discos